artist

Aime Jules Dalou was one of the most prolific and successful monument makers in France during the last two decades of the nineteenth century. Dalou received his first commission for a public monument for the Royal Exchange in London having been forced into exile to England because of his left-wing political views. This commission was a major turning point in the artist's career. When he returned to Paris after the amnesty of 1879-80, only monuments celebrating the greatest men of ideals of his era could completely satisfy him. In Paris during the 1890s, a number of Dalou's monuments were erected and inaugurated to commemorate distinguished individuals. Each of these individuals was someone with whom Dalou felt a particular artistic, social, or political affinity.

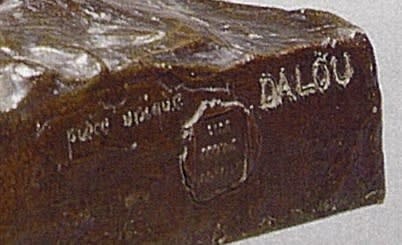

Adrien A. Hebrard (c. 1865-1937), fondeur, devoted much of his life to promoting sculpture and the craft of bronze casting. He was especially committed to the preservation of works left uncast by artists at the time of their death. Without Hebrard's intervention much of the work of Jules Dalou would have remained unknown. Three years after Dalou's death, the Petit Palais acquired a great number of small terracotta and plaster models. Two years later, in 1907, Hebrard was given authorization to cast the works in bronze.

literature

Ciechanowiecki, cat. 11, 16 and 17; Hunisak, p. 207-229, and figs. 105a-105W; Homage to A.A. Hébrard, see introduction.