artist

The following text is reproduced courtesy of independent curator Wendy McDaris (2005):

Roger Phillips was born in New York City in 1930. His education as a metal smith began on Long Island at age 12 as a blacksmith’s helper. He has worked in metal ever since. His first exposure to art was at the Woodstock Country School in Vermont where he studied with Francis Foster, a teacher from Black Mountain College who ran his classes on the Bauhaus model.

Phillips graduated from Bard College in 1953. He studied drawing and design at the New School and metal fabrication at the Jewish Museum in New York. He is a past president of the Artist-Blacksmith’s Association of North America. His studio/workshop is located in Stuyvesant, New York about 100 miles north of New York City.

A constructivist, Phillips is in private and public collections throughout the United States. A large portion of his work is kinetic, made of stainless steel and brightly painted aluminum plate. Many pieces are commissioned for specific outdoor sites. Smaller versions, suitable for the interior of a house, of some of Roger’s sculptures have been produced in limited editions.

The beauty of Roger Phillips’s sculpture is experienced as soon as you see it. Simplicity and purity are achieved through meticulous engineering and craftsmanship. His vision is elegant, positive and decidedly upbeat. His own words reveal the inner spirit of the work.

Several influences are obvious: the bright forms, although more geometric, are reminiscent of Alexander Calder; the smoothness of motion plays homage to George Rickey; and the dialogue between graphic and three dimensional work refers to Ellsworth Kelly.

Various kinetic sculptors use slightly different methods to create motion: in Calder’s work the moving elements are attached from the top, Rickey’s are pendulums, Tim Prentice uses ballast, Lin Emery connects at the bottom and Pedro de Movellan sometimes uses magnets. Each produces a different effect. In contrast, Phillips has the moving elements held at top and bottom so each moves in a 360-degree orbit around a vertical axis.

There is a provocative contrast between the rigidity of the frame and the fluidity of the moving elements. The moving parts seemingly disappear and reappear as they revolve, revealing the surrounding landscape through the negative space. The sculptures appear light and airy as their glossy colored surfaces reflect their natural surroundings.

Phillips’s sculpture recalls Plato’s description of geometric form: “these are not, like other things, beautiful relatively, but always and absolutely.”

Description

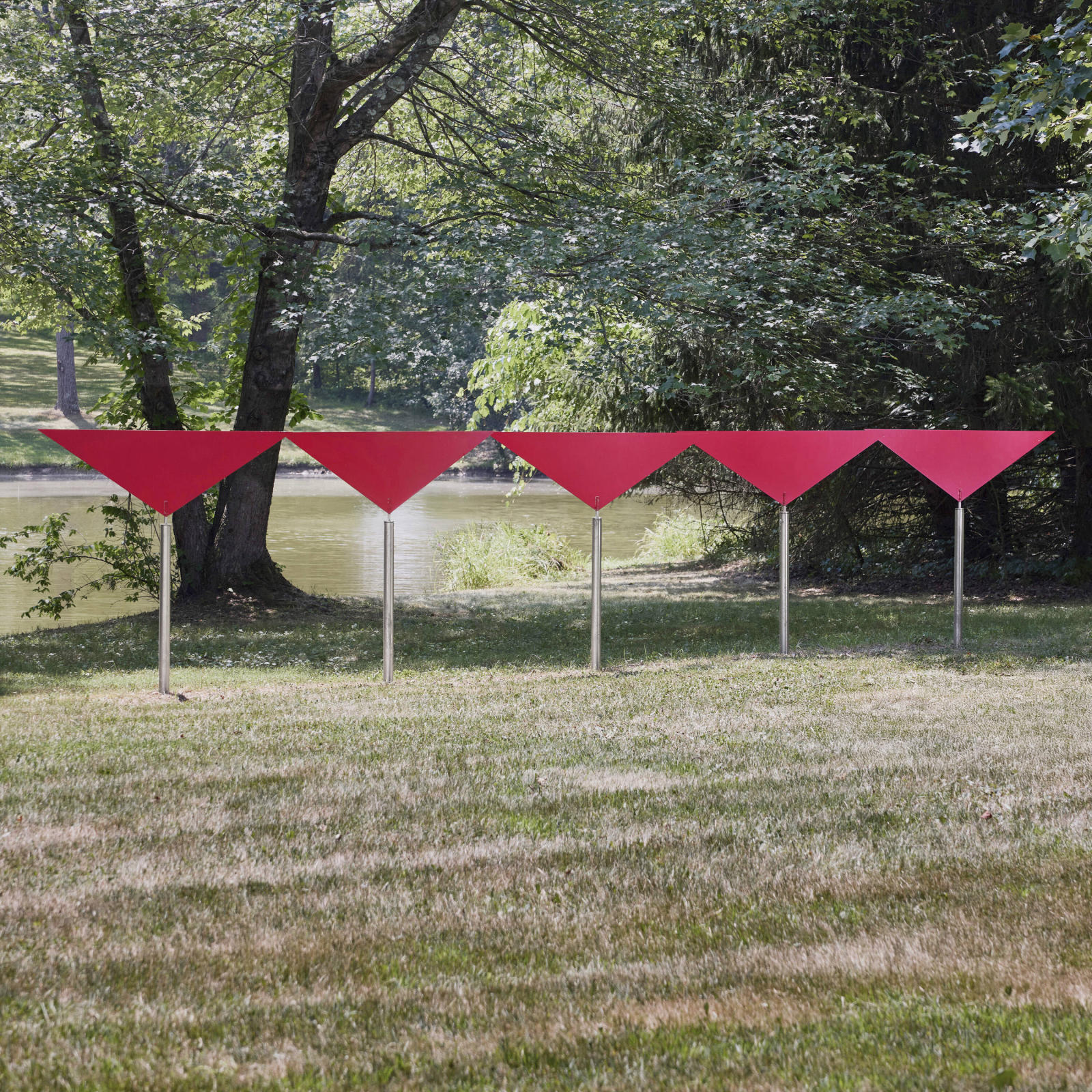

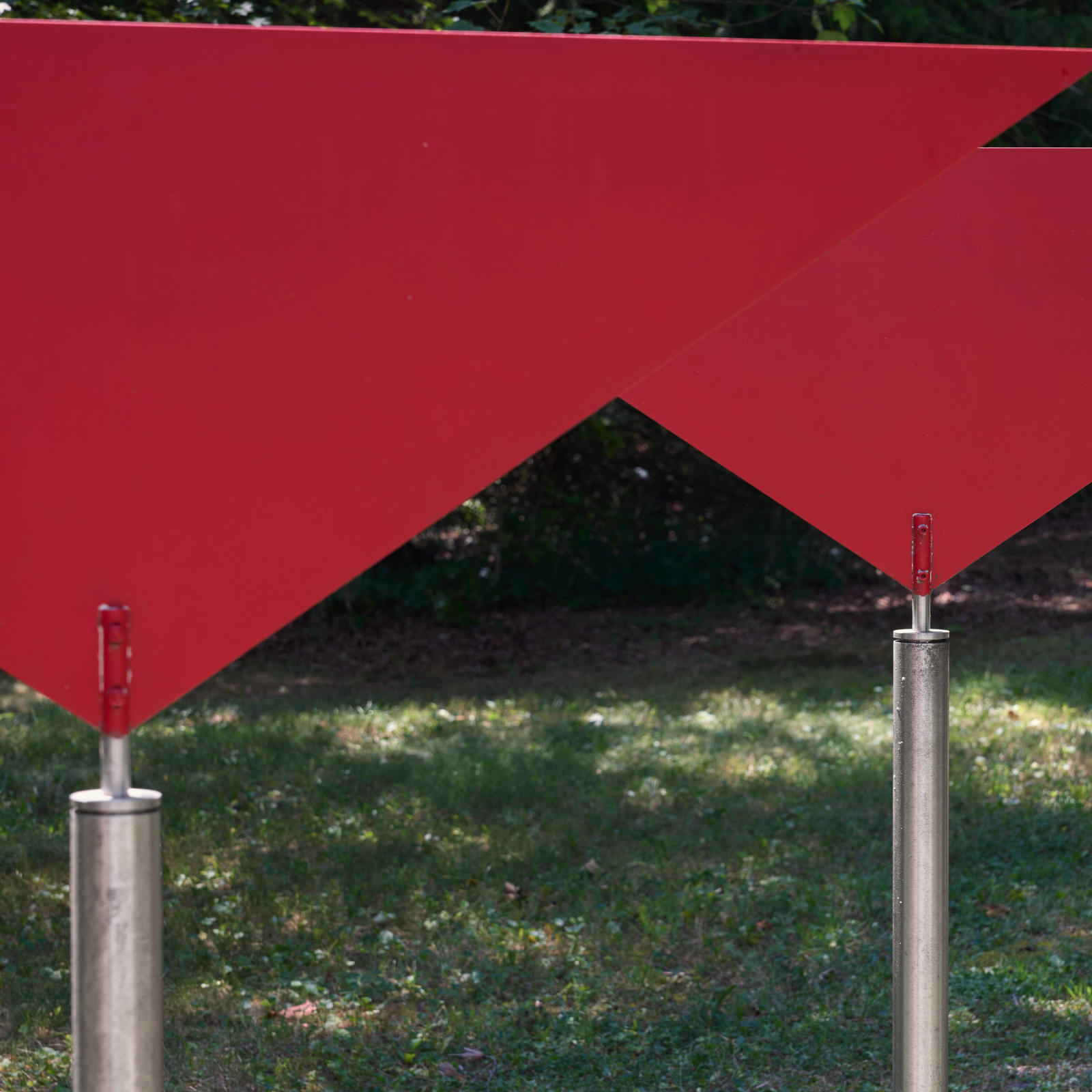

Five Triangles exemplifies Phillips’ long engagement with geometric form and motion in space. Here five identical red triangles, each mounted on slender stainless-steel poles, spin freely with the wind, an elegant synthesis of order and variability. The repetition of shape establishes a visual rhythm, solidifying the work as a cohesive whole, yet the kinetic element ensures that no two moments are the same. Each triangle turns independently, introducing an ever-changing relationship between the parts.

Elevated on slender stems, the forms align with the horizon more than the ground, freeing them from the earthbound weight typical of sculpture. They appear to hover lightly within the landscape, allowing air, light, and shadow to pass beneath and through them, amplifying their sense of buoyancy.

At 57 inches high, Five Triangles engages the landscape at a human scale, large enough to assert its presence, yet low enough to invite intimacy and movement around it. The red planes punctuate nature’s organic greens and browns with crisp geometry, creating a dialogue between the natural and the constructed. In this balance of structure and freedom, Phillips’ work affirms the kinetic tradition as one that animates not only form, but the viewer’s awareness of space, motion, and time.